A Quiet Farewell Beckons on the Horizon for Creedence Clearwater Revival’s Hidden Gem

In the spring of 1972, as the American music scene shifted beneath the shadow of social upheaval and change, Creedence Clearwater Revival found themselves navigating turbulent waters of their own. Their final studio album, Mardi Gras, arrived not with fanfare but with fracture—a band reeling from Tom Fogerty’s departure and caught in a crosscurrent of creative tensions. Amid the album’s divided heart, a modest song called “Sail Away”, written and sung by bassist Stu Cook, slipped quietly into the tracklist, offering a contemplative glance seaward and inward at the same time. It’s a subtle goodbye that whispers more than shouts, a measured breath before the curtain falls.

The Last Voyage of a Collapsing Fleet

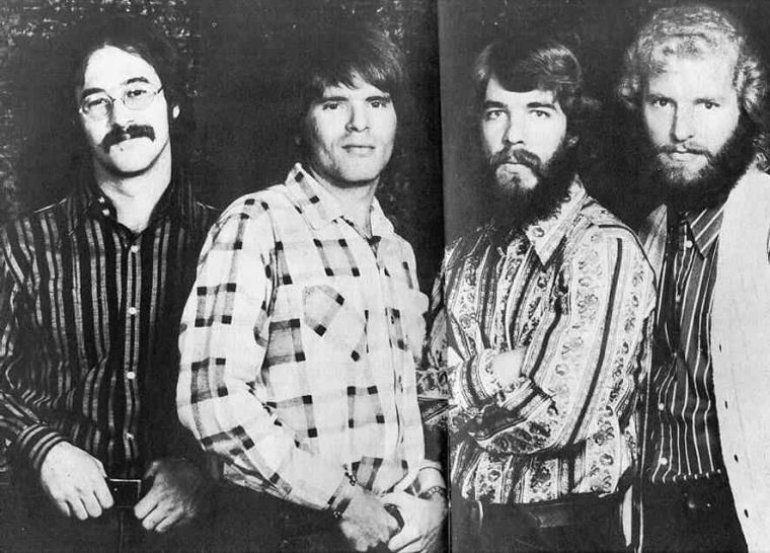

When Mardi Gras was released on April 11, 1972, it marked the end of an era. CCR had dominated charts and airwaves with hits that felt like distilled American life: the relentless beat of “Bad Moon Rising,” the triumphal wheels of “Proud Mary,” songs that surged like rivers swollen with rain—emotional, urgent, and unmistakably John Fogerty’s voice. But by the time of Mardi Gras, the band was no longer a cohesive force. Tom Fogerty, the rhythm guitarist and elder brother to John, had walked away, leaving John Fogerty, Stu Cook, and Doug Clifford to wrestle with the future. The album’s notoriously democratic approach—each member taking turns handling vocals and songwriting—felt less like a triumphant experiment and more like a reluctant compromise.

Into this uneasy mix came “Sail Away,” a two-minute-and-twenty-eight-second track that doesn’t storm or bluster but rather skims across the emotional surface with quiet resolve. The song was Cook’s moment to speak, and he did so with an unvarnished candor rare in CCR’s canon. While the album churned with conflicted energy, “Sail Away” offered a rare moment of stillness, almost like a diary entry scribbled in the aftermath of a quarrel. The metaphor is plain: a captain barking orders in the fog, heard only by the singer; the restless promise of leaving, of crossing the water to a place where there’s room to breathe.

A Song Written Between the Lines of Dissent

The “captain” figure in the lyrics has long been read as a stand-in for John Fogerty’s frustrating control over the band—a leadership style that breathed life into their hits but also sowed discord behind the scenes. Whether Cook intended the metaphor as such or simply painted with broad strokes, the effect is searingly intimate. The song acts like the quiet moment between storms, where fists unclench and the heart calculates its next move. “Sail Away” encapsulates the emotional weight of loss and escape, the resignation that sometimes leaving isn’t an act of rebellion but a necessary mercy.

Musically, the song is a microcosm of CCR’s signature sound but stripped down and reflective. The rhythm section—Cook’s own basin-deep bass and Clifford’s steady drumming—moves with a careful pace; the guitar doesn’t blaze but instead offers a hesitant, almost half-formed thought in its breaks. Cook’s vocals, talk-sung rather than soaring, ground the track in working-class frankness. This is a man stepping forward from the shadow of the Fogerty name, insisting on his own story, his own perspective. It’s this blue-collar humility that gives “Sail Away” its lasting emotional resonance—proof that not every turning point arrives with fanfares or fireworks.

The Quiet Heart of an Uneasy Album

Mardi Gras came with a peculiar duality. On one side, the radio-ready singles like “Sweet Hitch-Hiker” and “Someday Never Comes” were last gasps of CCR’s chart dominance, brash and unmistakably tied to John Fogerty’s voice and vision. On the other, the trio’s uneasy experiment of shared creative control spread like a fault line beneath the surface. Within this tension, “Sail Away” felt like a secret note, a pocket of calm between sharper, more aggressive statements.

In the album sequence, it plays a pivotal role. Positioned amid punchier, more direct tracks, the song’s steady, rolling rhythm acts as a kind of breath for the listener—a moment to feel the wooden deck of the ship rise gently with the waves before the next storm hits. It’s the kind of song that invites reflection, a whispered negotiation with one’s own regrets and hopes.

Reflecting years later, Stu Cook shared in a rare interview, “That song was about wanting to move on. Not because I was angry, but because some things just have to end for everyone’s sake.” His voice remains calm, measured—like the song itself—revealing the humanity of those final days. The departure wasn’t laced with drama but suffused with a need for mercy and peace.

More Than a Footnote in CCR’s Story

For decades, the story of CCR’s final days has been told through the lens of conflict and the magnetic force that was John Fogerty’s leadership. Yet “Sail Away” stands apart as a gentler chapter, a private note left on the table in the smoke-filled room after the last set. It reminds us that beneath the roaring hits and iconic riffs lies a band of men grappling with change, with fracture, with the last flicker of something shared and beloved.

Just as their biggest songs capture public triumphs and tragedies, “Sail Away” captures a moment only the insiders might glimpse—a man standing quietly by the rail, looking toward the horizon, exhaling the weight of farewell. It is transformation distilled to its essence: slow, steady, and irrevocable.

And sometimes, that is enough to fill an ocean.

You can almost hear the waves lapping the shore long after the music fades, as if the sea itself holds the secrets no words can fully tell.