When a band built its legend on snarling riffs and unshakable declarations, a track like “Take It Like a Friend” feels like a whispered farewell. It’s not the anthem you expect from Creedence Clearwater Revival, especially not on their last studio album, Mardi Gras. Instead, it’s a quiet reckoning folded into the fabric of a fractured band, a song that carries the weight of missed chances and the hard dignity of knowing when to let go.

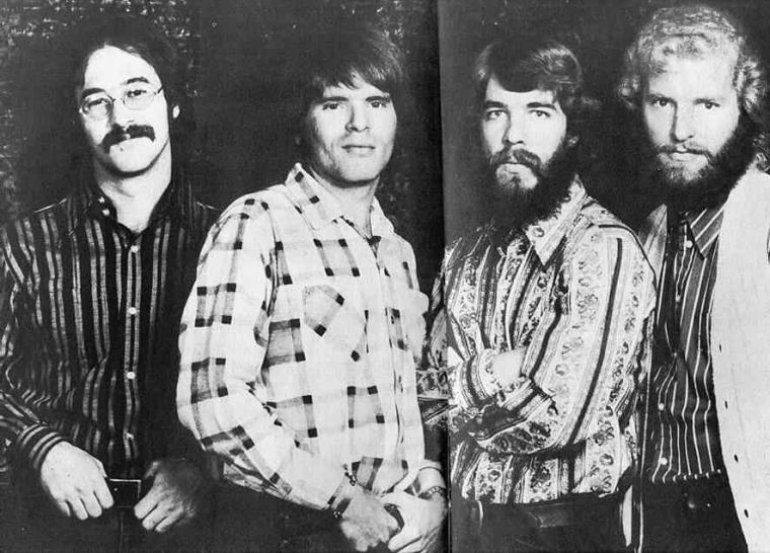

By April 1972, when Mardi Gras hit the shelves, CCR was a band unraveling in real time. Gone was Tom Fogerty, the rhythm guitarist and John Fogerty’s older brother, who had left amid simmering conflicts. The remaining trio—John Fogerty, bassist Stu Cook, and drummer Doug Clifford—attempted an uneasy truce in the form of an unusual album concept: distribute songwriting and lead vocal duties equally. It was meant to be a balm for egos bruised by overbearing control, but to most listeners, it sounded less like unity and more like a group stretching for a footing that none fully grasped.

Enter “Take It Like a Friend,” the second track, fronted by Stu Cook, a voice rarely spotlighted in the Creedence narrative. Cook didn’t just provide the bass on this one—he wrote it, sang it, owned it. The song’s lyric is deceptively simple, a domestic tableau painted in words that suggest a game gone bitter and a player stepping back without rancor. “Hope you take it like a friend,” Cook intones—not with bitterness, but with a weary politeness that feels both resigned and resolute.

There’s no theatrical bitterness here, no grandstanding melancholy. Instead, this song offers a lesson in civility amidst loss, a muted acknowledgment of a shared history unraveling: “Gather up your chips / I don’t want your hand.” The imagery evokes card games and social rules, a metaphor for creative territory and personal boundaries no longer respected. It’s a domestic disagreement disguised as a public song, a final note left on the kitchen table after the shouting has died down.

Listening now, decades later, “Take It Like a Friend” is perhaps the most human track on an album widely considered an uneasy swan song. It lacks John Fogerty’s trademark sheen—those mythic Americana tales spun with the certainty of a weathered stonemason carving his name into a mountain. Instead, Cook’s lean guitar work and direct, conversational vocal style ground the song in everyday reality, the plainspoken language of disappointment, not despair. The track doesn’t demand headlines or foot-stomping anthems; it wants only to be heard, understood in its ordinary sadness.

That ordinariness is the song’s quiet power. While earlier Creedence hits barreled ahead with undeniable momentum, “Take It Like a Friend” pauses, taking stock of what remains after claims and contests have been laid bare. There’s no triumph here—only a carefully measured retreat, an acceptance without bitterness, which feels tragically rare in rock narratives often dominated by bitterness and rebellion.

For longtime fans who grew up with Creedence’s roaring chronicles of rivers and working-class grit, this track is a moment frozen in amber: the reflection of a band confronting its own unraveling. As much as Mardi Gras aimed to share the spotlight, it served as a testament to fractured trust. Cook’s lead vocal and songwriting credit speak to an attempt at equality, but the fractured nature of the album reveals the wounds beneath the attempt. “Take It Like a Friend” becomes more than a song—it’s a document of retreat, an act of grace in a band slipping apart at the seams.

The album’s commercial performance told a quiet story too: respectable chart positions driven less by groundbreaking work and more by a previously sealed reputation. There was no bold new direction here, only a band navigating the tricky shoals of internal politics and personal pride. In that sense, the song doubles as a rare confession, a bittersweet whisper amid the noise of those final sessions, trying—and failing—to patch a rift with melody and quiet words.

What remains most striking is the song’s tone, a maturity that feels pulled from a later place of understanding. There’s an unusual generosity in its restraint—it doesn’t shout about loss, it offers it gently, as if saying, “This is over, but let’s not make enemies of it.” It’s a moral economy, a small kindness, a practice in bowing out with a little grace intact. That mature sensibility makes Stu Cook’s voice resonate for listeners who have known their own reckonings, who have felt the strange mixture of regret and relief that can follow any ending.

Unlike the band’s more thunderous farewells, “Take It Like a Friend” asks fans to accept a subtler truth: sometimes ending isn’t a battle to be won; it’s a peace to be honored. It lives in the quiet spaces where pride meets pragmatism, where hurt cedes to history, and where the simple dignity of walking away without malice becomes a kind of victory in its own right.

For anyone who’s ever held onto the echo of a fading friendship or the fading chords of a once-great band, this song brings a familiar ache. It is not a triumphant anthem but a parting glance, a door closing softly with a whisper, not a bang.

Maybe that’s what makes it linger long after the last note fades: the sound of a friend saying goodbye without turning their back.